The global electrocoat market is estimated to grow from $3.08 billion in 2016 to $3.80 billion by 2021, at a CAGR of 4.34 percent between 2016 and 2021. This market is witnessing moderate growth because of demand for e-coat from end-use industries such as automotive and appliances.

Ron LewarchikElectrocoating is a process that uses an electrical current to deposit an organic coating from a paint bath onto a part or assembled product. Due to its ability to penetrate recesses and thus coat complex parts and assembled products with specific performance requirements, electrocoat is used worldwide throughout various industries to coat a wide swath of products including those in automotive, appliance, marine, and agriculture. Electrocoat, and specifically cathodic electrocoat, has enabled a dramatic improvement in corrosion resistance over that offered by anodic electrocoat or other more conventional methods of coating.

Ron LewarchikElectrocoating is a process that uses an electrical current to deposit an organic coating from a paint bath onto a part or assembled product. Due to its ability to penetrate recesses and thus coat complex parts and assembled products with specific performance requirements, electrocoat is used worldwide throughout various industries to coat a wide swath of products including those in automotive, appliance, marine, and agriculture. Electrocoat, and specifically cathodic electrocoat, has enabled a dramatic improvement in corrosion resistance over that offered by anodic electrocoat or other more conventional methods of coating.

Cathodic electrocoat is available in multiple technology types, most notably is epoxy cathodic and acrylic cathodic.

- Acrylic cathodic is expected to experience the highest growth in the e-coat market. Cathodic acrylic e-coat is typically used in applications that require UV durability as well as corrosion protection on ferrous substrates. It is also used in applications where light colors are required.

- Cathodic acrylic e-coat is available in a wide range of glosses and colors to provide both exterior weathering and corrosion protection. Acrylic cathodic is used as a one-coat finish for agricultural implements, garden equipment, appliances, and exterior HVAC.

The application of electrocoat involves four steps:

- Pretreatment2: After the parts are cleaned, a pretreatment is applied to prepare the metal surface for electrocoating.

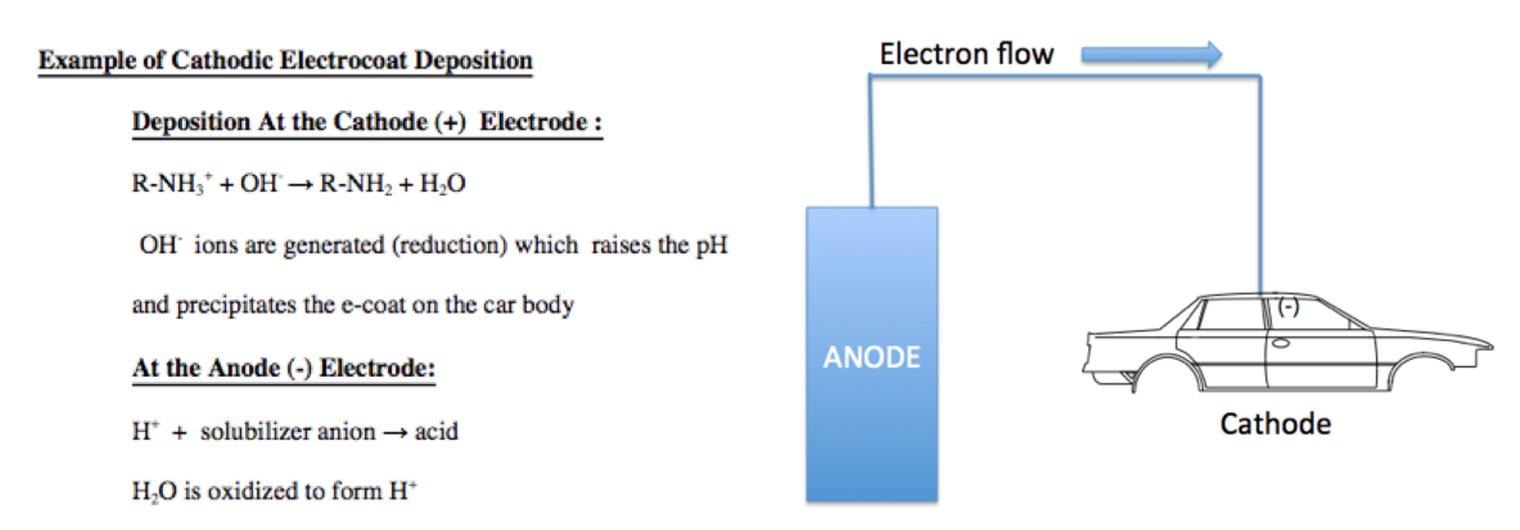

- Electrocoat Application: Positively charged cathodic paint is deposited on the electrically conductive substrate from a cathodic paint bath using direct current. The positively charged paint is deposited at the negatively charged cathode where reduction takes place.

- Post Rinses: Parts are rinsed to reclaim undeposited paint solids.

- Bake: Paint is baked to thermally cross-link the paint and volatilize water as well as any residual organic solvents.

In step 2, paint particles are deposited on the surface of the electrically conductive substrate to form an insulating film. The rate of the film deposited diminishes with time as the conductivity of the paint surface has an insulating effect as the film increases in film thickness. At this point, the deposited film has very little water and solvent present so the water post rinses (step 3) do not have a negative effect on the deposited film. The coated substrate is then baked to eliminate water and remaining volatile as well as to crosslink the polymeric film.

Figure 1As figure I indicates, in cathodic electrodeposition, the positively charged paint is attracted to the negatively charged cathode where reduction occurs, resulting in the liberation of hydrogen gas. At the anode, oxidation occurs with the accompanying release of oxygen. The deposited paint film coalesces into a relatively insoluble paint film and after one or more water rinses, the deposited paint film enters a bake oven to enable the crosslinking of the cathodic paint film.

Figure 1As figure I indicates, in cathodic electrodeposition, the positively charged paint is attracted to the negatively charged cathode where reduction occurs, resulting in the liberation of hydrogen gas. At the anode, oxidation occurs with the accompanying release of oxygen. The deposited paint film coalesces into a relatively insoluble paint film and after one or more water rinses, the deposited paint film enters a bake oven to enable the crosslinking of the cathodic paint film.

The advantages and disadvantages of cathodic electrocoat include:

- Excellent corrosion resistance, even at lower film thicknesses

- Offers excellent resistance to bimetallic corrosion (when dissimilar metals are in contact)

- Frequent color change is not practical

Many cationic epoxy electrocoat resins are comprised of a Bisphenol A based epoxy resin comprised of amine groups that are neutralized with a low molecular weight acid such as formic, acetic, or lactic acid. Since the coating bath has a pH of slightly below 7, bath components are comprised of stainless steel or other corrosion-resistant materials to prevent rust formation.

The most common crosslinker is a blocked isocyanate, so once the coating is baked, the blocked isocyanate is activated and reacts with available hydroxyl and amine groups. Other components of a typical electrocoat bath include pigment, filler pigment, water, solvent, and a low level of modifying resins such as plasticizers and flexibilizers, flow modifiers and catalysts.

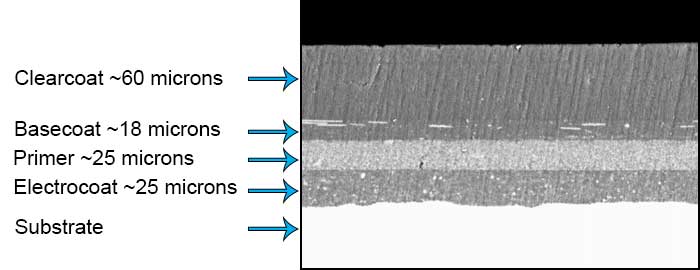

Ecoat is used because it provides superior corrosion protection as it coats surfaces that are inaccessible by conventional means. Film thickness is uniform without any defects such as sags, runs, or edge beads. Electrocoat is also very cost-effective as it provides nearly 100 percent material utilization with good energy efficiency and a relatively low cost per square foot of applied coating.

Throwpower is the ability of an electrocoat to penetrate into “hard to reach” areas, such as the inside of a hollow metal object. Dependent on the applied voltage, bath solids, conductivity, deposition time, bath temperature, solvent levels, and proper tank agitation, deposition time, throwpower and coating appearance can be optimized.

A simple dip-applied coating cannot effectively coat the interior of complex-shaped parts, as during the bake process, the water/solvent has a washing effect in the interior portions of the part that prevents adequate film build. At the time an electrocoated object is removed from the bath, most of the water and solvent are squeezed from the electrocoat so that during the bake the washing effect is minimal as compared to that of a simple dip-applied coating.

The film build of electrocoat paint is self-limiting as the film becomes more insulative as the thickness of the film approaches its maximum. Higher voltage and longer immersion times will permit higher film builds until the maximum possible film build is reached, which is normally about 1.0 mil and 1.2 mils.

Voltage is normally between 225 and 400 volts. If the voltage is too high, there will be a film rupture of the coating applied to the outer surfaces. This is called the rupture voltage. At a sufficiently high voltage, the current will break through the film, leading to gas generation under the film (hydrogen for cathodic and oxygen for anodic).

Other factors that affect film build include bath temperature and conductivity. Immersion times are normally on the order of 2-3 minutes.

In summary cationic electrocoating is expected to grow at a faster rate than that of more conventional product finishing processes as it provides excellent corrosion protection for complex shapes, low volatile organic content and lastly, acrylic cationic electrocoat also offers resistance to UV light for exterior applications.

Ron Lewarchik is President of Chemical Dynamics, and brings 40 years of paint and coatings industry expertise to his role as a contributing author. Chemical Dynamics is a full-service paint and coatings firm specializing in consulting and product development based in Plymouth, Michigan. Since 2004, he has provided consulting, product development, contract research, feasibility studies, failure mode analysis and more for a wide range of clients, as well as their suppliers, customers and coaters. He has also served as an Adjunct Research Professor at the Coatings Research Institute of Eastern Michigan University. As such, Ron was awarded a sub-grant from the Department of Energy to develop energy-saving coating technology for architectural applications, as well as grants from private industry to develop low energy cure, low VOC compliant coatings. He taught courses on color and application of automotive topcoats, cathodic electro-coat and surface treatment. His experience includes coatings for automotive, coil, architectural, industrial and product finishing. Previously, Ron was the Vice President of Industrial Research and Technology, as well as the Global Director of Coil Coating Technology for BASF (Morton International). During his fourteen-year tenure with the company, he developed innovative coil coating commercial products primarily for roofing, residential, commercial and industrial building, as well as industrial and automotive applications. He was awarded fifteen patents for new resin and coating formulas. From 1974 to 1990, Ron held positions with Desoto, Inc. and PPG Industries. He was the winner of two R&D awards for coatings utilizing PVDF resins, developed the first commercial high solids automotive topcoat and was awarded 39 U.S. patents for a variety of novel technologies he developed. He holds a Masters in Physical Organic Chemistry from the University of Pittsburgh and subsequently studied Polymer Science at Carnegie Mellon University.