The plating shop owner couldn’t believe his eyes. There it was written in black and white in the lab report.

As finishing operators learn more about the presence of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in materials used around the electroplating process, some are growing concerned they may already have what is termed the “forever chemicals” in their lines and systems.

Recently, the Midwest plating operation conducted a preliminary test of its wastewater discharge to see if PFAS were present. They had heard about EPA and States suspecting PFAS in wastewater discharged from plating lines and feared inspections may be on the horizon.

It turns out the shop owner had a reason to be concerned: the facility — which we are not naming in this article to gain approval to share their story — received a positive test result.

They then set out to find out how PFAS got into their system.

Determing How it Came In

Some shops are discovering that PFAS contamination is coming into their system from their customer’s parts, which often undergo a machining operation that utilizes oils and cutting fluids that have traces of PFAS in those products“We were shocked,” the owner says. “Nothing we have used in the past gave us any indication we would have traces in our system, but there it was. Of course, we had the issue of finding out how it got there.”

Some shops are discovering that PFAS contamination is coming into their system from their customer’s parts, which often undergo a machining operation that utilizes oils and cutting fluids that have traces of PFAS in those products“We were shocked,” the owner says. “Nothing we have used in the past gave us any indication we would have traces in our system, but there it was. Of course, we had the issue of finding out how it got there.”

As the U.S. EPA begins sending questionnaires to over 1,800 plating shops in early 2023 inquiring about the presence of PFAS in processes on site— and with an inspection of their wastewater discharge likely soon to follow by the EPA — many shops that thought they were safe and clear from possible PFAS contamination in their systems are finding they may not be.

And just like the Midwest shop that spent several weeks talking with suppliers to find out if something they used in their lines may have triggered the positive PFAS result, they are coming to the conclusion that is even more bewildering: the PFAS is hiding in plain sight.

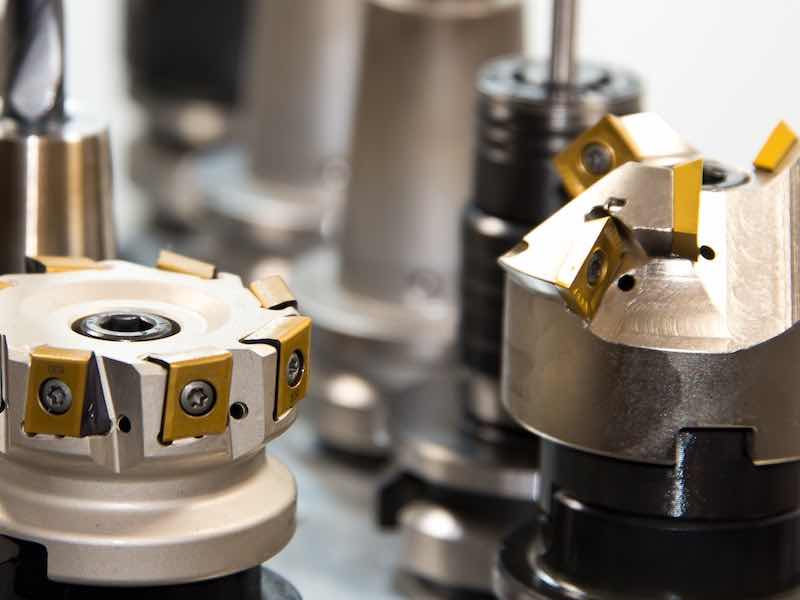

Their shop and many others are discovering that PFAS contamination is coming into their system from their customer’s parts, which often undergo a machining operation that utilizes oils and cutting fluids that have traces of PFAS in those products.

“It came in on the parts,” the Midwest owner says. “We assume it was fluids or oils at the machine shop or some other type of application they put on the parts. They sent it to us, we cleaned and pretreated the parts, and then finished them. But we are the ones who ended up with PFAS in our wastewater treatment system and filters.”

‘The Customer Has it in Their Facility’

That was the same predicament faced by a finishing shop in the New England region. They, too, tested onsite systems and discovered traces of PFAS in wastewater, even though the company had never used fume suppressants in the past or performed any hex chrome operations.

“We spent a few weeks trying to figure out how it happened,” says the owner, whom FinishingAndCoating.com has also agreed not to identify. “Finally, we started looking at the parts that were coming in, and that is where we traced it. The customer had it in their facility when they machined the parts.”

As word trickles out anecdotally about how shops are getting PFAS into their system through outside sources, it has heightened the concern amongst shops who say they are keeping an eye out for any possibilities.

“Anytime the EPA gets involved, it is very concerning,” says a shop owner in the Southeast U.S.

“In light of EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap, the manufacturing and related business sectors can expect enhanced scrutiny of effluent with regard to the possible presence of PFAS.”

What can shops do if they discover they are not the source of the contamination but rather their customer’s products that came in through their loading dock? Legal experts say that is a tricky slope because plating shops need customers to stay in business.

“We live in a brave new world indeed,” says Lynn Bergeson, an attorney, and managing partner at Bergeson & Campbell, a firm in Washington D.C. that has been representing businesses in cases brought by the U.S. EPA for several decades.

“We all are beginning to appreciate the ubiquity of PFAS in items/articles/products of all sorts and of which we were unaware,” Bergeson says. “In light of EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap, the manufacturing and related business sectors can expect enhanced scrutiny of effluent with regard to the possible presence of PFAS.”

Scrutiny on Finishing Industry to Increase

Lynn BergesonBergeson says the U.S. EPA and state regulatory agencies are laser-focused on blunting further water and groundwater contamination, and she “would expect such scrutiny to increase, not abate.”

Lynn BergesonBergeson says the U.S. EPA and state regulatory agencies are laser-focused on blunting further water and groundwater contamination, and she “would expect such scrutiny to increase, not abate.”

Business entities need to query their upstream suppliers, Bergeson says, and ask about the chemical components of the materials they are receiving. Supplier certifications will help identify the source of the PFAS as a first step. Depending upon the source, she says finishers can make informed judgments about their customer’s supplier and whether an alternative supplier can provide the item without PFAS.

“The process is tedious but essential,” Bergeson says. “Without undertaking the requisite due diligence, finishers can stumble their way into multi-party litigation for liability arising from property contamination, tort liability/personal injury, contractual liability — such as failure to warn, fitness for purpose, etc. — not to mention reputational injury, diminution on stock value, and related business challenges.”

Beth GotthelfTwo attorneys at Butzel Long in Michigan who specialize in environmental law and have worked with dozens of finishing operators across the country say the problem of parts contaminated with PFAS substances is very real.

Beth GotthelfTwo attorneys at Butzel Long in Michigan who specialize in environmental law and have worked with dozens of finishing operators across the country say the problem of parts contaminated with PFAS substances is very real.

“We heard about this very early on,” says Beth Gotthelf, who is also general counsel to a Michigan surface finishing trade group. “Finishers can’t afford to bear the cost of treating PFAS on their own when the source is coming from a variety of sources, including customers and the municipality supplying the water to the facility. This is in addition to the PFAS that was in fume suppressants used to comply with EPA regulations.”

Because of the chance that PFAS is coming into finisher’s facilities on parts, Gotthelf says shops should have a definitive conversation with their customer about what lies ahead.

“Finishers may talk to their customers about sources and warn the customers that the finisher may need to stop treating the customer’s parts until they find another solution or ask that customer to help pay PFAS treatment costs,” she says. “That is where we are at.”

Susan JohnsonButzel Long’s Susan Johnson says that as the EPA digs deeper into what manufacturing products, such as oils and fluids, contain PFAS, the issue will become more widespread.

Susan JohnsonButzel Long’s Susan Johnson says that as the EPA digs deeper into what manufacturing products, such as oils and fluids, contain PFAS, the issue will become more widespread.

“If some of the proposed revisions to the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) reporting come about, I think we’ll find more and more parts that have PFAS associated with them,” Johnson says. “I think everyone is going to have to start asking up and down the supply chain about emerging contaminants, and PFAS specifically.”

Review Customer Agreements to Disallow PFAS

Finishers should review their customer agreements to make sure they disallow any PFAS — whether intentionally added or otherwise — in products procured under those agreements.

“At the least such contractual provisions help shift liability and provide defenses,” Bergeson says. “Businesses also need to be mindful of the complexity of these issues and remain informed. Detractors will never be persuaded that ignorance is a compelling defense.”

While part contamination is a fairly new phenomenon that platers have to worry about when it comes to PFAS, the legacy use of PFAS has been a constant issue for many shops that used fumed suppressants years ago in — at the time — was a safety feature.

Living up to its term as the “forever chemicals,” shops now worry they can never rid themselves of PFAS in their tanks and wastewater treatment because it stays there for seemingly forever.

“We all are probably going to have some type of PFAS in systems or in waste,” the owner says. “It is coming at us from many places, including customer products.”

A Midwest chrome plater says they used fume suppressants in the past not to meet stack tests but rather to protect their employees’ health by limiting employee exposure.

“Our control equipment meets the stack limits easily with HEPA filters,” the shop owner says. “The cost was about $60,000 a year to use the suppressants; we felt it was worth it to keep exposure as low as possible. Looking back, maybe it was a bad decision now.”

Meanwhile, the plater has also been advised by their legal counsel — and the consulting lab that does much of their testing — to not test their waste system for PFAS until federal and state regulators set firm limits.

“We all are probably going to have some type of PFAS in systems or in waste,” the owner says. “It is coming at us from many places, including customer products.”

EPA Will Eventually Discover the Issue

Ethan WareOne of the foremost experts in legal issues between finishing operations and the EPA is Ethan Ware, an attorney with Williams Mullen in Columbia, South Carolina, who has spoken at numerous plating and anodizing conferences over the past few years.

Ethan WareOne of the foremost experts in legal issues between finishing operations and the EPA is Ethan Ware, an attorney with Williams Mullen in Columbia, South Carolina, who has spoken at numerous plating and anodizing conferences over the past few years.

Ware suggests EPA will eventually discover that products used in the manufacture and machining of parts may have PFAS in them and that the agency will work its way to investigating the finishing shops that handle those parts. There are at least three ways EPA may be able to acquire this information.

First, he says EPA published a proposed regulation earlier this year suggesting a change to TSCA guidelines, which will require companies to undertake efforts to “reasonably ascertain” whether or not PFAS constituents have been used at their facilities over the last 10 years. The owner will have to inventory those PFAS uses and disclose them under the proposed rule, even if the PFAS components are incorporated into an article — which is typically excluded from EPA reporting.

“I think all of us would be naive to think that this situation is not going to ever come to light,” Ware says of parts with PFAS making their way to finishing operations. “There’s likely going to be a recordkeeping and reporting obligation under these new TSCA rules that are going to require reporting, and plating lines will have to disclose the presence of PFAS in products and processes onsite. When that happens, EPA is going to follow up with all of us.”

Some machine shops and stamping manufacturers use cutting fluids that contain PFAS.Second, in August 2022, the EPA proposed to designate two of the most widely used PFAS substances as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA): perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), including their salts and structural isomers. The decision to list PFOA and PFOS on the list of hazardous substances is based on what EPA says is significant evidence they may present a substantial danger to human health or welfare or the environment.

Some machine shops and stamping manufacturers use cutting fluids that contain PFAS.Second, in August 2022, the EPA proposed to designate two of the most widely used PFAS substances as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA): perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), including their salts and structural isomers. The decision to list PFOA and PFOS on the list of hazardous substances is based on what EPA says is significant evidence they may present a substantial danger to human health or welfare or the environment.

Additionally, EPA says the proposed rule would — in certain circumstances — require making the polluter pay by allowing EPA to seek to order cleanups or recover EPA cleanup costs from owners or operators of sites where PFOA or PFOS are released or otherwise discharged into the environment. This liability is regardless of fault and cannot be passed off to the suppliers.

Just as Bergeron says that ignorance is not a defense, Ware adds finishing shops will not be able to point the finger at customers if they discover PFAS that came in on machined or manufactured parts. He says CERCLA liability does not apply to the purchaser of the plater’s finished product.

“The liability is going to be triggered whether they had any intent to take in PFAS compounds or not when PFAS constituents are detected onsite,” Ware says. “What do they do when they get a form that says to certify that there is no PFAS suspected in their wastewater discharge? That’s going to take some guts for those in the industry to sign that certification.”

Finally, under the EPA PFAS Plan from 2019, States are beginning to require “monitor and report” for PFAS constituents in wastewater under NPDES and pretreatment discharge permits. The data will be used to create a data bank of information about what types of shops are detecting PFAS in wastewater. When a company seeks renewal of its wastewater permit, of course, the owners and operators are required to certify the accuracy of the information provided in the Form 2C application, including whether or not PFAS are “suspected present” in the wastewater.

“That could be catastrophic for us in the surface finishing industry because you have to investigate, then you have to make an inquiry,” Ware says. “No, you don’t have to test. But you have to look at the SDS, and you have to look at any process profiles on your chemicals to see if they do contain PFAS.”

Shops Report Delay in Vital Info From Suppliers

Numerous shops have already ascertained from their chemical suppliers whether their products contain any form of PFAS that may potentially register in their wastewater discharge. Often they get the all-clear signal, but some shops have reported a delay in getting that vital information from a few supplier companies.

Numerous shops have already ascertained from their chemical suppliers whether their products contain any form of PFAS that may potentially register in their wastewater discharge. Often they get the all-clear signal, but some shops have reported a delay in getting that vital information from a few supplier companies.

A Michigan plating shop owner says they annually send a formal letter requesting information to chemical suppliers on whether any of the chemicals sold to them contained PFAS or PFOA substances.

“All suppliers responded, and none of the chemicals we purchase contain PFAS or PFOA,” the owner says. They have not yet begun the process of talking to their customers about the substances being on parts, but they are very concerned about what they may find.

“We have heard of other shops tracing PFAS back to being in the metalworking fluids from customers,” the owner says.

Some shops worry that given the extremely low threshold levels that the EPA and other regulatory agencies are setting for PFAS — some are in the parts per quadrillion — they believe the water they are getting from municipalities may already be enough to set off PFAS alarms.

“It is an issue given the very low limits and that we are responsible for the water coming into our facility upstream,” the owner says. “If someone else is contaminating the water and the water enters our facility, we become liable for the effluent discharge.”

In addition, Ware also says that beginning in 2024, all manufacturers and finishers will need to disclose if they use more than 100 pounds of a “persistent bio-cumulative toxin,” which PFAS is deemed by the EPA.

That PBT reporting requirement is even more worrisome because of their low threshold for reporting.

Catastrophic for Surface Finishing Industry

“That could be catastrophic for us in the surface finishing industry because you have to investigate, then you have to make an inquiry,” Ware says. “No, you don’t have to test. But you have to look at the SDS, and you have to look at any process profiles on your chemicals to see if they do contain PFAS.”

In simplistic terms, Ware says finishing shops should stop using any products they suspect has PFAS in them and undertake what EPA calls a “reasonable inquiry” to find out if the raw or process materials — such as cutting or machining fluids — used in their customer’s manufacturing process contain these contaminants.

“We can stop the use of them going forward or minimize it so that we don’t have significant liability for cleanup as well,” he says.

A Mid-States plater says they foresee the PFAS situation becoming even more worrisome for the finishing industry since the EPA has named it as a targeted industry in its PFAS Roadmap.

“This will become a big issue for everyone in the next 3 to 5 years,” says the plater, who adds that it will be difficult to track what parts coming into their shop may have issues. “We get products from all over the world, and it is hard to know who machined every part we process.”

Contact Butzel Long at https://www.butzel.com; Bergeson & Campbell at https://www.lawbc.com; and Williams Mullen at https://www.williamsmullen.com

Sources for PFAS Information

- U.S. EPA: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained

- American Chemistry Council: https://www.americanchemistry.com/chemistry-in-america/chemistries/fluorotechnology-per-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

- State of Michigan: https://www.michigan.gov/pfasresponse/faq/categories/pfas-101

- State of Wisconsin: https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/PFAS

- Centers for Disease Control: https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/PFAS_FactSheet.html

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/index.html