We have reported Fe–Pt films with hard magnetic properties electroplated from plating baths using citric acid as a complexing agent.

The present study focuses on glycine as a new complexing agent instead of citric acid. We developed an electroplating process of Fe–Pt films using glycine-based plating baths and then investigated the effect of Cl ions on the coercivity. High coercivity could be obtained around the film’s composition of Fe50Pt50, and the obtained value (∼1000 kA/m) was almost the same as that in the previous study of the citric acid-based plating bath. The amount of glycine slightly affected the coercivity and the Fe content in the film, and under our experimental conditions, 20 g/l of glycine was effective in obtaining a high coercivity. From the investigations of the effect of Cl ions on coercivity, we confirmed that the coercivity reduction by the presence of the Cl ions does not depend on the complexing agent and concluded that complexing agents are not a factor in the decrease of coercivity by the presence of the Cl ions in the baths.

I. Introduction

L10 Fe–Pt films have attracted attention as magnets for small medical devices due to their excellent biocompatibility and superior hard magnetic properties.1–3 Various methods are used to fabricate Fe–Pt films, such as sputtering, vapor deposition, and electroplating. Some researchers developed fabrication processes of L10 (Fe, Co)–Pt thick films using electroplating and reported good hard magnetic properties.4–8 We have also developed a fabrication process of Fe–Pt thick films using electroplating and reported Fe–Pt films with good hard magnetic properties using citric-acid-based plating baths.9

The magnitude of the demagnetizing field for film magnets differs in the in-plane direction and out-of-plane one, and the demagnetizing field for the out-of-plane direction is higher than that for the in-plane one (the permeance coefficient for the out-of-plane direction is small). If the coercivity of the film magnet is low, the magnetic flux density at the operating point becomes much smaller than the remanence. Therefore, the coercivity value is important, and high coercivity is required for the film magnets.

We reported Fe–Pt thick films electroplated from plating baths containing different concentrations of NaCl and pointed out the possibility of coercivity enhancement by Na ions.10 Our recent study investigated the effect of Cl ions in the plating baths on the hard magnetic properties of the Fe–Pt films and reported that the Cl ions decrease the coercivity, indicating that the Cl ions are not suitable for obtaining the Fe–Pt films with high coercivity.11

The present study focuses on glycine, the simplest stable amino acid, instead of citric acid as a complexing agent, to investigate the effect of the complexing agent on the reduction of coercivity by the Cl ions. Firstly, we developed an electroplating process of Fe–Pt films using glycine-based plating baths and then investigated the effect of Cl ions on the coercivity.

IIi. Experimental Procedures

A. Electroplating

Fe–Pt films (≈10 μm in thick) were prepared on Cu substrates using electroplating. Table I shows bath conditions. We employed ammonium amide sulfate to improve the Pt reagent’s solubility, and the plating bath’s pH was adjusted at ∼2 using sulfuric acid. (The same pH for the citric-acid-based bath.9) In Sec. III B, FeCl2 and NH4Cl were used to add Cl ions in the baths. Table II shows the plating conditions.

Table 1: Bath conditions.

| Reagents | Contents for Sec. III A | Contents for Sec. III B |

| FeSO4 · 7H2O | 1–6 g/l | 2–x (g/l) |

| FeCl2 · 4H2O | ⋯ | x = 0–2 g/l |

| Pt(NO2)2(NH3)2 | 10 g/l | 10 g/l |

| Glycine (C2H5NO2) | 10–40 g/l | 10–40 g/l |

| NH4NH2SO3 | 30 g/l | 30 g/l |

| NH4Cl | 0–40 g/l | 0–40 g/l |

| H2SO4 | 0.25 mol/l | 0.25 mol/l |

Table 2: Electroplating conditions.

| Conditions | Values |

| Bath temperature | 70 °C |

| Anode/cathode (substrate) | Pt mesh/Cu plate (0.5 mm in thick) |

| Current density | 1 A/cm2 |

| Plating area | 5 × 5 mm2 |

| Plating time | 15 min |

B. Annealing

The as-plated Fe–Pt films have disordered fcc structures, and the disordered phase was magnetically soft. To transform the disordered phase to the ordered L10 (fct) one, we annealed the as-plated films at 700 °C under a vacuum (≈10−3 Pa) using a furnace. The temperature was ramped from room temperature to 700 °C at 100 °C/min, then kept constant for 5 min. These annealing conditions were determined based on our previous study.12

C. Measurements

The thicknesses and the compositions of the as-plated films were measured at 25 points and nine ones with a micrometer (Mitutoyo CPM15-25MJ) and a scanning electron microscope-energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) system (Hitachi High-technologies S-3000), respectively. We determined the thickness and the composition by averaging the obtained values. The hysteresis loops of the annealed Fe–Pt films were measured with a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). The maximum applied field was ∼2 MA/m for the loop measurements, and we obtained the coercivity from the loop.

III. Results and Discussion

A. Investigations of plating conditions

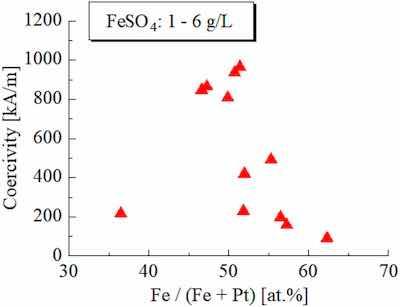

FIG. 1. Relationship between Fe composition and coercivity.Since we employed glycine as a new complexing agent in this experiment, we first investigated bath composition and plating conditions to obtain high hard magnetic properties.

FIG. 1. Relationship between Fe composition and coercivity.Since we employed glycine as a new complexing agent in this experiment, we first investigated bath composition and plating conditions to obtain high hard magnetic properties.

Generally, Fe–Pt alloys have high magnetocrystalline anisotropy around the composition of Fe50Pt50 and show high coercivity. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of the Fe composition of the as-plated Fe–Pt films on the coercivity of the annealed ones. The evaluation result is shown in Fig. 1. In this experiment, we varied the Fe composition by changing the Fe reagent concentration in the plating bath from 1 to 6 g/l.

As shown in Fig. 1, we could obtain high coercivity around the Fe50Pt50 composition, and this result is consistent with the expected behavior based on the variation in the magnetocrystalline anisotropy constant.

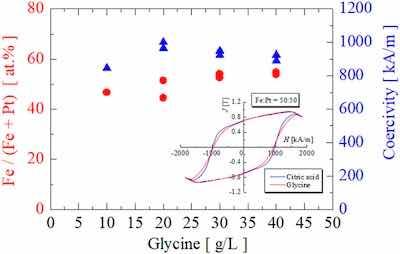

FIG. 2. Fe composition of the as-plated Fe–Pt films and the coercivity of the annealed ones as a function of the amount of the glycine in the plating bath.Figure 2 shows the Fe composition and the coercivity as a function of the amount of glycine in the plating bath. The inset indicates the hysteresis loops of the annealed Fe–Pt films with high coercivity prepared from the citric-acid-based bath and the glycine-based one. In this experiment, we fixed the Fe reagents at 2 g/l. As shown in Fig. 2, the Fe composition slightly increased with the increase in glycine. The coercivity showed almost the same value in the glycine amount from 10 to 40 g/l. In our experimental conditions, a high coercivity of 1000 kA/m was obtained at 20 g/l; this value was the same as that for the citric acid-based bath, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2.

FIG. 2. Fe composition of the as-plated Fe–Pt films and the coercivity of the annealed ones as a function of the amount of the glycine in the plating bath.Figure 2 shows the Fe composition and the coercivity as a function of the amount of glycine in the plating bath. The inset indicates the hysteresis loops of the annealed Fe–Pt films with high coercivity prepared from the citric-acid-based bath and the glycine-based one. In this experiment, we fixed the Fe reagents at 2 g/l. As shown in Fig. 2, the Fe composition slightly increased with the increase in glycine. The coercivity showed almost the same value in the glycine amount from 10 to 40 g/l. In our experimental conditions, a high coercivity of 1000 kA/m was obtained at 20 g/l; this value was the same as that for the citric acid-based bath, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2.

B. Effect of Cl ions on coercivity

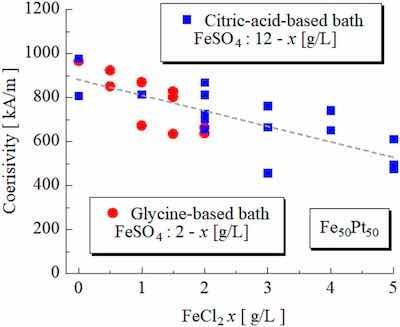

FIG. 3. Coercivity of the annealed Fe–Pt films as a function of the amount of the FeCl2 in the plating bath.As mentioned in “Introduction,” in our previous study on the coercivity for the citric-acid-based baths, a coercivity reduction effect was observed by the presence of Cl ions in the plating baths.11 In this section, we investigated the effect of Cl ions on coercivity using glycine-based baths.

FIG. 3. Coercivity of the annealed Fe–Pt films as a function of the amount of the FeCl2 in the plating bath.As mentioned in “Introduction,” in our previous study on the coercivity for the citric-acid-based baths, a coercivity reduction effect was observed by the presence of Cl ions in the plating baths.11 In this section, we investigated the effect of Cl ions on coercivity using glycine-based baths.

Figure 3 shows the coercivity of the annealed Fe–Pt films as a function of the amount of FeCl2 in the plating bath. We added Cl ions to the plating bath by partially replacing FeSO4 with FeCl2. The result for the citric-acid-based bath is also shown in Fig. 3. To control the film’s composition at Fe50Pt50, the amount of Fe2SO4 was set at 2 g/l for the glycine-based baths and 12 g/l for the citric-acid-based ones. As shown in Fig. 3, the coercivity decreased with increasing the FeCl2, indicating that a large amount of Cl ions in the plating baths is unsuitable for obtaining high coercivity.

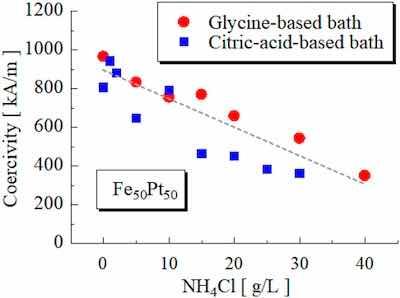

FIG. 4. Coercivity of the annealed Fe–Pt films as a function of the amount of the NH4Cl in the plating bath.As another approach to adding Cl ions in the baths, we investigated adding NH4Cl. Figure 4 shows the coercivity of the annealed Fe–Pt films as a function of the amount of NH4Cl, together with the result for the citric-acid-based bath. As shown in Fig. 4, the coercivity decreased with an increase in the NH4Cl concentration. This result suggests that the reduction of coercivity by the presence of Cl ions does not depend on the complexing agent.

FIG. 4. Coercivity of the annealed Fe–Pt films as a function of the amount of the NH4Cl in the plating bath.As another approach to adding Cl ions in the baths, we investigated adding NH4Cl. Figure 4 shows the coercivity of the annealed Fe–Pt films as a function of the amount of NH4Cl, together with the result for the citric-acid-based bath. As shown in Fig. 4, the coercivity decreased with an increase in the NH4Cl concentration. This result suggests that the reduction of coercivity by the presence of Cl ions does not depend on the complexing agent.

From Figs. 3 and 4, we found that complexing agents are not a factor in the reduction of coercivity by the presence of the Cl ions in the baths.

IV. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study developed a plating process of Fe–Pt films using glycine-based plating baths and investigated the effect of Cl ions on the coercivity. The results obtained are summarized as follows:

- High coercivity was obtained at the film composition around Fe50Pt50. The obtained value of 1000 kA/m was almost the same for the citric-acid-based baths.

- The amount of glycine slightly affected the composition and did not obviously affect the coercivity from 10 to 40 g/l.

- The Fe–Pt films prepared from the glycine-based baths with Cl ions showed lower coercivity than Cl ions-free baths. This result suggests that complexing agents are not a factor in reducing of coercivity due to the presence of Cl ions in the baths.

Written by Takeshi Yanai; Naoki Ogushi; Yuito Yamaguchi; Daiki Fukushima; Akiho Hamakawa; Akihiro Yamashita; Masaki Nakano; and Hirotoshi Fukunaga. Nagasaki University, 1-14 Bunkyo-machi, Nagasaki 852-8521, Japan. This paper was presented at the 16th Joint MMM-Intermag Conference.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions: Takeshi Yanai: Funding acquisition (equal). Naoki Ogushi: Data curation (equal). Yuito Yamaguchi: Data curation (equal). Daiki Fukushima: Data curation (equal). Akiho Hamakawa: Data curation (equal). Akihiro Yamashita: Funding acquisition (equal). Masaki Nakano: Funding acquisition (equal). Hirotoshi Fukunaga: Funding acquisition (equal).

References

1. T. Huang, J. Cheng, and Y. Zheng, “In vitro degradation and biocompatibility of Fe–Pd and Fe–Pt composites fabricated by spark plasma sintering,” Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 35, 43–53 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2013.10.023

2. W. F. Liu, S. Suzuki, D. S. Li, and K. Machida, “Magnetic properties of Fe–Pt thick-film magnets prepared by RF sputtering,” J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 302, 201 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2005.08.019

3. H. Aoyama and Y. Honkura, “Magnetic properties of Fe–Pt sputtered thick film magnet,” J. Magn. Soc. Jpn. 20, 237 (1996). https://doi.org/10.3379/jmsjmag.20.237

4. R. Bernasconi, A. Nova, S. Pané, and L. Magagnin, “Electrodeposition of equiatomic FePt permanent magnets from non-aqueous electrolytes based on ethylene glycol,” J. Electrochem. Soc. 169, 072506 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/ac81f8

5. P. L. Cavallotti, M. Bestetti, and S. Franz, “Microelectrodeposition of Co–Pt alloys for micromagnetic applications,” Electrochim. Acta 48, 3013 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-4686(03)00367-0

6. O. D. Oniku, B. Qi, and D. P. Arnold, “Electroplated thick-film cobalt platinum permanent magnets,” J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 416, 417 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2016.05.044

7. J. Ewing, Y. Wang, and D. P. Arnold, “High-current-density electrodeposition using pulsed and constant currents to produce thick CoPt magnetic films on silicon substrates,” AIP Adv. 8, 056711 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5007272

8. D. Liang and G. Zangari, “(Invited) Electrochemical deposition of Fe–Pt magnetic alloy films with large magnetic anisotropy,” ECS Trans. 50, 35 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1149/05010.0035ecst

9. T. Yanai, K. Furutani, T. Ohgai, M. Nakano, K. Suzuki, and H. Fukunaga, “Fe–Pt thick-film magnets prepared by electroplating method,” J. Appl. Phys. 117, 17A744 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4918698

10. T. Yanai, J. Honda, R. Hamamura, H. Yamada, N. Fujita, K. Takashima, M. Nakano, and H. Fukunaga, “Effect of Na ions in plating baths on coercivity of electroplated Fe–Pt film-magnets,” J. Alloys Compd. 752, 133 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.04.126

11. T. Yanai, D. Fukushima, R. Narabayashi, N. Ogushi, Y. Yamaguchi, A. Yamashita, M. Nakano, and H. Fukunaga, “Reduction effect of coercivity of electroplated Fe–Pt film magnets by chloride ion in plating baths,” AIP Adv. 14, 025020 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1063/9.0000776

12. T. Yanai, Y. Omagari, S. Furutani, A. Yamashita, N. Fujita, T. Morimura, M. Nakano, and H. Fukunaga, “High-temperature properties of Fe–Pt film-magnets prepared by electroplating method,” AIP Adv. 10, 015149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5130466