Ensuring that the powder is fluidizing properly is essential to a successful powder coating application.

Fiona Levin SmithSo what is fluidizing? Basically, it uses air to turn powder into a ‘liquid’ state. A good fluidizing hopper will often have the appearance of a simmering pot of stew. But why do we need to fluidize the powder, though? Well, by fluidizing powders, they become easier to apply – both in terms of an even application and how smoothly the powder flows through the guns.

Fiona Levin SmithSo what is fluidizing? Basically, it uses air to turn powder into a ‘liquid’ state. A good fluidizing hopper will often have the appearance of a simmering pot of stew. But why do we need to fluidize the powder, though? Well, by fluidizing powders, they become easier to apply – both in terms of an even application and how smoothly the powder flows through the guns.

Check out some of the more common fluidization issues we’ve all experienced below. Some of these are common problems, others not so much, but we will delve into the problem, the cause, and some prevention tips and solutions.

Powder Blowing Out and Around the Hopper

The title is pretty self-explanatory as to how this issue appears, and you will know it when you see it. Typically, the powder acts this way when the powder level itself or the fluidizing pressure is too high – it can also be a combination of these two. Other causes of this issue are the powder being too fine, blocked hoppers, and poor venting.

So, how do we solve this? Let’s work our way through the list above. First up, powder levels. A good idea is to mark a level on the fluidizing hopper that acts as a guideline for what to never exceed. A good guideline to follow is that the hopper should never be more than 2/3 full. This way, you will know when the hopper is, or is close to being, overfilled.

As for the powder being too fine, you first need to establish if the powder is too fine due to the percentage of virgin to reclaim or because the manufacturer has made the particle size too small. If it is the former, and you reclaim powder yourself, increase the percentage of virgin to reclaim. As for the latter issue, contact the manufacturer and relay the problem so you can discuss with them the next steps.

Reclaim powder is hygroscopic, which means that it will pull moisture from the air if given a chance. If the reclaimed powder is too fine and sucks up a lot of moisture, you may start to get fluidizing problems – the sort that ends up with you cranking up the psi or fluidizing pressure on the hopper to compensate for the heavier particles. Solve this by having a good, clean air supply and perhaps fluidizing the powder for half an hour or so before spraying to liberate some of the moisture from the powder particles. Virgin powder must be clean and very dry, so if it isn’t, this is a good step to take.

No Air Percolating Through the Surface of the Powder

Simply put, this issue is when the air is not penetrating the powder. Usually, the cause of this is insufficient air pressure, a clogged membrane, a blocked membrane, too fine powder, or the powder itself has become compacted.

Typically, the powder should be in a rolling state, where the air is evenly distributed through the fluidizing membrane and the powder. If this is not the case, check your airlines and the air pressure, and look for any kinks, damages, or blockages in the hoses. Clogged membranes, either damaged or contaminated with oil or water, need to be replaced. No ifs, and’s, or buts; if you have a clogged membrane, it’s got to go.

Moving onto blocked membranes (which are not the same as clogged membranes), the way to solve this issue is to, shockingly, clean the blockages. If the powder is too fine, adjust the ratio of virgin to reclaim. And lastly, if the powder has become compacted, for whatever reason, you have to break it back up with a clean, wooden stirring device and fluidize it with dry air. Take care not to damage the fluidizing membrane at the bottom of the hopper with the stirring device, though.

Also, do keep a sharp eye on your ratio of reclaim to virgin, as too much reclaim will cause the powder to perform differently and may also cause back ionization to occur.

Stratification

Sometimes, powders will stratify in the hopper. Stratification is when particles – due to different weights – separate into different layers during fluidization. This is particularly common with unbonded metallics (which we have covered here), where the different gravities of the metallic flakes and the powder will cause them to separate. Such separation causes the color of the coating to shift in pigmentation and the uniformity of the sparkle effect (if it is metallic) to fluctuate.

Stratification in other powders does not show quite as easily as it does with metallics. So, to solve this particular issue with metallics, you will either need to use bonded metallics or reduce the fluidizing pressure. Or both! Also, manually mixing the powder particles back together, and adding more virgin, can help, depending on the scenario.

Concerning metallics, if you are reclaiming them, you want to keep the ratio around 80% virgin to 20% reclaim to keep the color uniform.

Two Top Tips from the Experts?

As we covered above, there are a fair number of ways for a job to go wrong when it comes to fluidization. Blockages, stratification, gun spits, the works. So, to pre-empt the issues above, we have compiled a few extra tips.

One, control the humidity of the room as best you can. The more humidity in the air, the more risk you run of the powder absorbing moisture. Or worse yet, if the application room itself is hot and humid, the particles will begin to clump together before they even hit the substrate. Now, if these clumps form inside the hopper, they can cause all sorts of chaos. At best, they will cause small gun spits. At worst, they will start to build up in the pump, hose, or inside the gun and grow larger until they either block the hose or come loose in a surge.

Two, preventive maintenance is going to be your best bet when it comes to avoiding issues in this area. Fluidizing membranes have a life expectancy, and many manufacturers recommend checking them at least once a year. Keeping them clean, especially free of oil and water, based on the manufacturer’s specifications, will save you some pain. As for fluidizing in general, at IFS Coatings, we honestly recommend checking your equipment every day. Do it all; pumps, hoppers, guns, pick-up tubes, membranes, and hoses. Better to find a broken piece of equipment in the morning than halfway through an application, right?

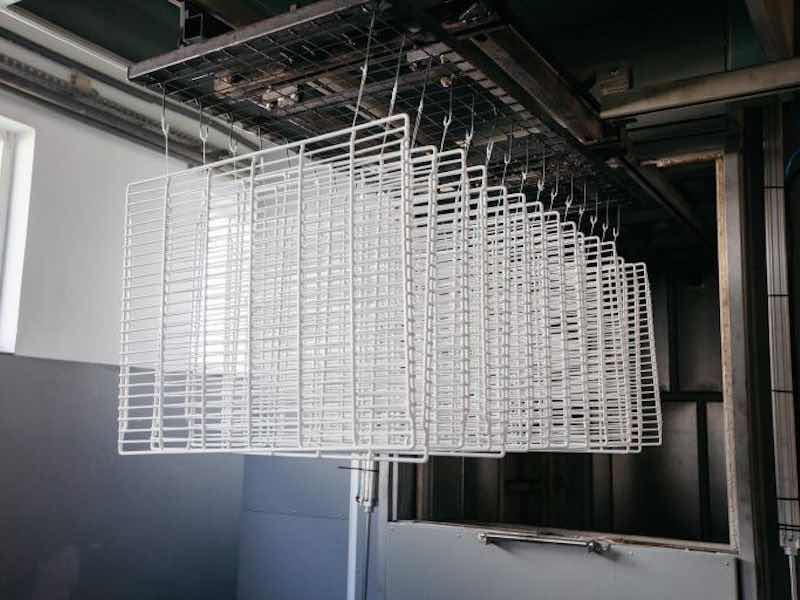

Fluidizing Beds

These days, most coating lines, large or small, use hand or automatic powder guns to apply their powder. However, fluidized beds are an older way of applying powder coatings, and though they are probably not as widely used as they once were, they are still in use today. Not as common as they once were, they still have their place and, of course, still have a set of potential issues that go with them. Some job shops favor them – typically

for small parts and valve bodies – so we are going to cover some of the issues you might come across in using them.

So, just what are fluidizing beds? Given that these are not overly common anymore, you may recognize fluidizing beds by sight rather than by name. Basically, a fluidizing bed fluidizes by virtue of a fluidizing plate or membrane (now say that out loud three times fast). This plate is plastic and filled with hundreds of thousands of small holes - think of an air hockey table – which the air is diffused through, thereby creating a curtain of air that keeps powder suspended.

While we’re on this, there are two ways that fluidizing beds are used. The first is where you heat the part and then run it through a fluidized bed. This causes the powder to adhere, melt, and fuse to the part. After this, the part goes into the oven, and the powder is cured. The second manner of using fluidized beds is when an electrostatic charge is applied during the coating process.

Why aren’t fluidizing beds popular? For the most part, money. Fluidizing beds, by virtue of their size, require a lot of power and powder to get going. Also, they are not as efficient or product-saving as spraying by handgun or on an automatic line. As better equipment became available over the years, fluidizing beds fell out of popularity for these reasons.

Fluidizing Bed Issues

There is all manner of ways for jobs to go wrong. Fluidizing beds, just like with most job shop equipment, come with their own particular baggage. Let’s jump right into it, starting with:

Particle Size

If the powder, due to reclaiming or efforts on the manufacturer’s part, is too fine, it can cause all manner of trouble. With a fluidizing bed, the powder that is too fine can cause irregular coverage. Keeping a close eye on the powder levels and the actual amount of powder on the bed is a smart idea.

Pick-up tubes are usually positioned roughly an inch above the bottom of the fluidizing membrane. If you have too much powder flowing into the hopper, it will sink to the bottom and cause all sorts of problems. Newer equipment circumvents issues like this by having many settings that you can adjust depending on what the job needs.

Part Temperature and Dwell Time

If your job shop uses the method where you preheat the substrate before moving it through the powder application process, then you should pay close attention to the temperature and dwell times.

Depending on the part’s thickness, density, shape, and recommended dwell time, the temperature it is heated needs to be adjusted. Suppose the part is too hot; the heat with fuse loose particles together before they even touch the part. Similarly, powder not making it to the area can be heated and fused by the part passing through the fluidized bed. These clumps will float around the fluidized bed and will eventually sink to the bottom. If they are not screened out using a filter, they can also cause rat holing as they build up on the membrane and block air holes.

Now, if you leave a part in the bed for longer than advised, the film build will continue to thicken. As many job shops know (and dread), the thick film builds can cause appearance issues from orange peel to sagging to discoloration of clear coats.

It goes without saying that paying super close attention to the temperature of the part going into the fluidized bed and the amount of time it spends in there (line speed) is essential.

Air Supply and Rat Holes

A bad air supply – bad either from damaged equipment, clogs, or not being clean – is an issue that crops up a lot. Not just in fluidizing beds but all around. The bad air supply can muck up an application, inter-coat adhesion, and, crucially for this guide, the fluidizing plates. If the air is contaminated by grime, dirt, oil, or water, those particles will cling to any surface they can – and that’s if they don’t contaminate the powder itself.

But we are talking about fluidization beds right now, and boy, howdy, does a dirty air supply mess everything up. Fluidizing plates, in particular, have issues when the holes in the membrane get blocked. As said, holes are tiny; it does not take much for them to become clogged, and once they are, you get a problem called rat holing.

An ugly name for an ugly problem, right? Rat holes are basically when, due to clogged air holes, the air, and therefore the powder, pushes through unevenly across the fluidized bed. Where the air does push through, it is more concentrated and causes geysering.

Speaking of contamination, typically, if a job shop uses fluidized beds, they have multiple beds for different chemistries to avoid cross-contamination between formulas, and they can also swap them out for color changes. Sometimes this means separate fluidized beds, and other times it means using a roll-on/roll off system where they can swap out beds as needed. Keep this in mind when considering your own systems.

To Wrap Up

Fluidizing beds may not be as commonly used as they once were, but they are still a solid piece of equipment for those using them. They have their share of problems, what with needing a set amount of powder to function and daily maintenance, but keep them clean, mind your powder levels, and follow our tips for good fluidization, and you’ll be golden.

Fiona Levin-Smith is Vice president of Marketing and Specification for IFS Coatings. For further questions or inquiries, visit www.ifscoatings.com