Over the past 30 years, the utilization of lasers has revolutionized manufacturing.

Chance Willis, IPG Photonics; Luis Fernández, PPG; and Michael Cukier, Whirlpool.Specifically, lasers increase precision and efficiency while proving highly versatile across various materials. In-line barcoding and other laser marking applications have lowered costs while simplifying serialization and traceability. Lasers have also transformed sheet metal cutting economics in just twenty years. Laser welding first penetrated productivity-driven industries like consumer electronics and automotive over ten years ago, but is now reaching job shops in a handheld format. Matured laser applications like additive manufacturing, surface cleaning and surface modification are transforming manufacturing today.

Chance Willis, IPG Photonics; Luis Fernández, PPG; and Michael Cukier, Whirlpool.Specifically, lasers increase precision and efficiency while proving highly versatile across various materials. In-line barcoding and other laser marking applications have lowered costs while simplifying serialization and traceability. Lasers have also transformed sheet metal cutting economics in just twenty years. Laser welding first penetrated productivity-driven industries like consumer electronics and automotive over ten years ago, but is now reaching job shops in a handheld format. Matured laser applications like additive manufacturing, surface cleaning and surface modification are transforming manufacturing today.

A common thread is that lasers initially penetrate productivity-focused, quality-centric industries where enhanced throughput and precision drive operating expense (OpEx) savings, which overcome higher capital expenditure (CapEx). As equipment costs fall and an ecosystem emerges, laser penetration expands into lower volume and CapEx sensitive sectors. For laser heating, the future is now.

Speed and Low Energy Consumption

Whirlpool powder coating operations at the Greenville, Ohio KitchenAid plant.The first commercial laser heater deployments for lithium-ion battery cell electrode drying are underway. The unprecedented speed and low energy consumption of laser drying disrupts battery-making economics. In the coatings industry, market leaders have joined forces, targeting first adoption in powder coating markets with a dual focus on productivity and sustainability. After proving its value to powder coaters, it is expected that laser curing and drying will expand into liquids, adhesives, varnishes and other coatings in the fullness of time.

Whirlpool powder coating operations at the Greenville, Ohio KitchenAid plant.The first commercial laser heater deployments for lithium-ion battery cell electrode drying are underway. The unprecedented speed and low energy consumption of laser drying disrupts battery-making economics. In the coatings industry, market leaders have joined forces, targeting first adoption in powder coating markets with a dual focus on productivity and sustainability. After proving its value to powder coaters, it is expected that laser curing and drying will expand into liquids, adhesives, varnishes and other coatings in the fullness of time.

Like many liquid coatings systems, powder coatings are cured in convection ovens where the curing time can be defined as [1] “peak metal temperature, i.e., the maximum temperature attained by the substrate. Therefore, it takes a longer time to reach the recommended curing temperature in the case of a coating on an object having a large thermal mass.” In general [2], powder coatings typically crosslink “between 130°C-180°C” and require typical oven residence times around 10-20 min. The extended curing time dictates long ovens of “5 meters or more” to sustain reasonable throughput.

For these and other reasons, laser curing represents an opportunity to reduce the energy required to cure coatings in an industrial setting. For example [3], in a typical automotive production facility primarily using liquid coatings, the paint shop “consumes the largest quantity of energy during the vehicle manufacturing processes,” curing ovens represent a significant portion, second only to the painting booths.

A close parallel is curing by infrared (IR) lamps, but lasers have several advantages. While both technologies convert electricity to light roughly equally, a laser beam may be shaped to deposit energy only on the target surface.

Abhinandin et al.’s [1] first detailed investigation of laser curing in 1999 reported “although significant progress has been made in the formulation of various powder coatings, a matching effort in developing new curing technologies seems to be lacking.” Utilizing the CO2 gas lasers available then, the authors realized industrial quality curing in under a minute. Gas lasers convert just ~10% of electrical power into light and are difficult to project uniformly over large surfaces. The advent of near-infrared diode lasers, able to uniformly deliver tens of kilowatts over meter scale surfaces with power conversion efficiencies above 50% (Fig. 1), has brought laser curing of powder coat to the forefront.

For instance, in a 2010 study [4], a defocused (1.8mm spot size) 1.5kW 940nm diode laser was used to locally cure a PPG Industries epoxy-polyester hybrid resin. Although the “experimental set-up produced coating areas of a very narrow width, unsuitable for practical purposes”, Simone concluded that “local laser curing could enable multiple potential cost benefits including shorter process duration and reduced energy expenditure.”

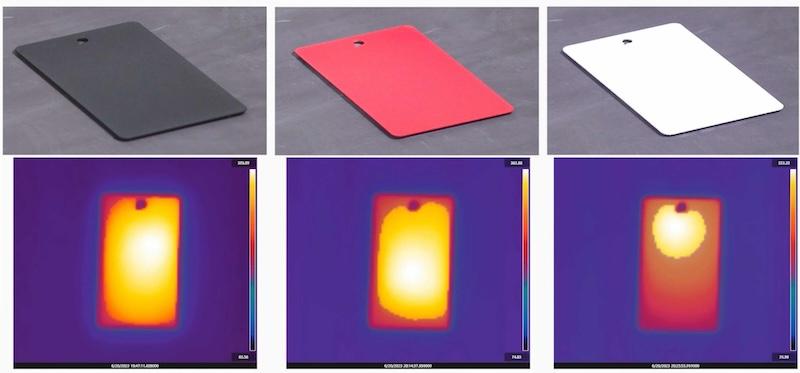

Visible (above) and FLIR (below) images of laser curing of powder-coated coupons. The FLIR camera captures the powder transition into a continuous coating, which occurs within seconds, but at different rates controlled by the thickness and optical qualities of the powder formulation.

Visible (above) and FLIR (below) images of laser curing of powder-coated coupons. The FLIR camera captures the powder transition into a continuous coating, which occurs within seconds, but at different rates controlled by the thickness and optical qualities of the powder formulation.

Short Curing Times in Room Temperature Curing Cell

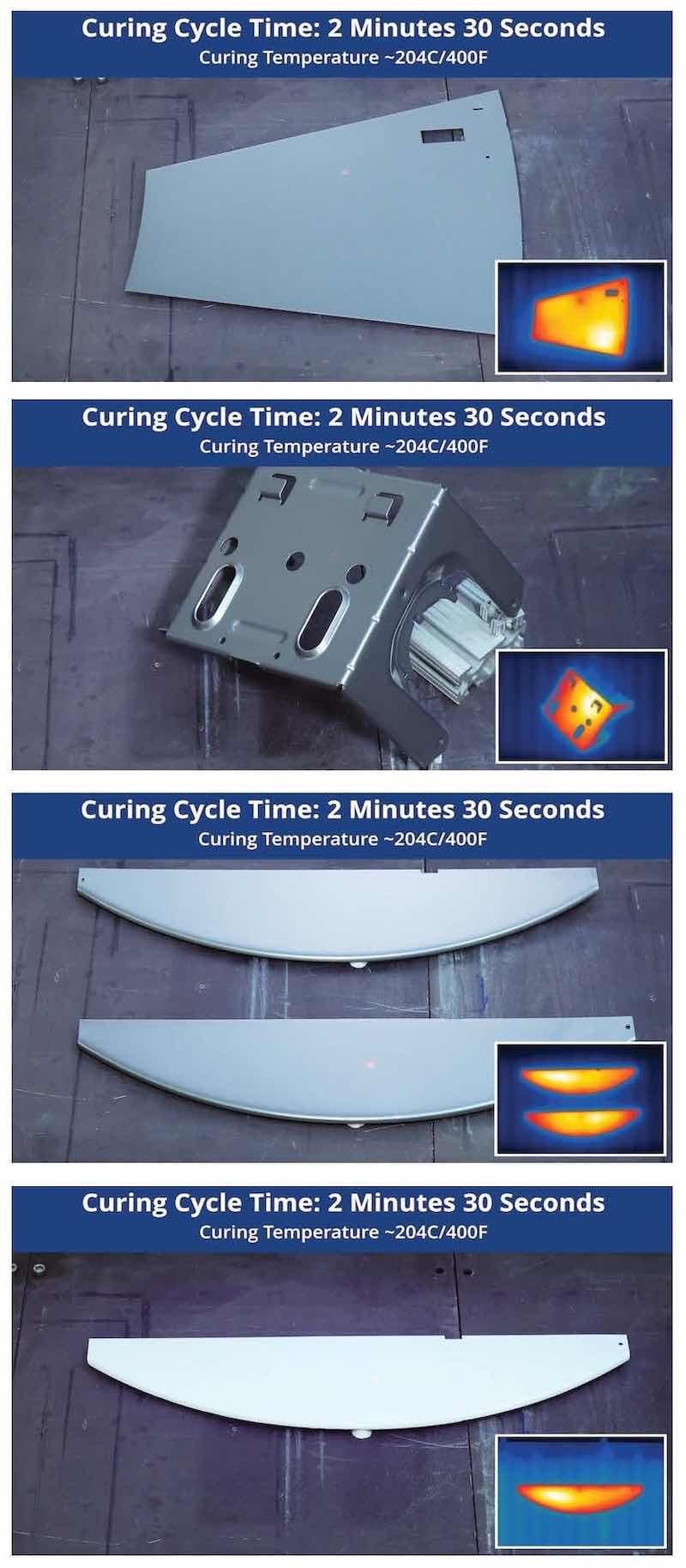

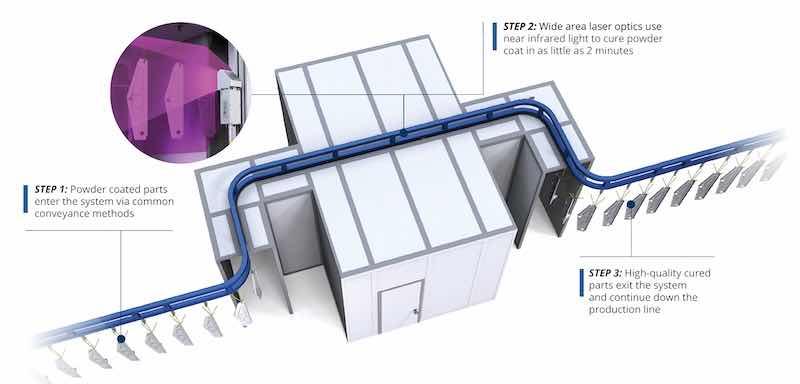

Various parts and cure time using lasers.Given the strong value proposition and sustainability potential of laser curing of powder coatings, industrial manufacturing companies in multiple markets are beginning to target first adoption. The interest stems from short curing times achievable in a room-temperature curing cell (for reference, “cell” refers to an enclosure into or through which parts are conveyed for laser exposure). We routinely achieve curing times of just a few minutes using infrared diode lasers, for example, on the part shown in this video.

Various parts and cure time using lasers.Given the strong value proposition and sustainability potential of laser curing of powder coatings, industrial manufacturing companies in multiple markets are beginning to target first adoption. The interest stems from short curing times achievable in a room-temperature curing cell (for reference, “cell” refers to an enclosure into or through which parts are conveyed for laser exposure). We routinely achieve curing times of just a few minutes using infrared diode lasers, for example, on the part shown in this video.

We attribute the short curing time to volumetric heating based on the laser’s ability to penetrate the full coating thickness. A major contributor is the infrared laser’s ability to dramatically shorten to just a few seconds the time required to convert the powder from solid particles to a continuous coating, a gelling process, as captured in this video. Lasers preferentially heat the coating, not the part or the surroundings. This can yield huge energy savings in common cases where a bulky metal part comprises most of the thermal load.

In contrast, a convection oven process is surface-limited. The entire part must reach curing temperature, while much of the energy heats the surroundings, meaning minutes of pre-heating are required to reach the gel temperature before curing can begin. Standard American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) performance tests have demonstrated that powders cured via laser generate similar results to those cured using conventional ovens.

A close parallel is curing by infrared (IR) lamps, but lasers have several advantages. While both technologies convert electricity to light roughly equally, a laser beam may be shaped to deposit energy only on the target surface. In contrast, IR lamps are blackbody radiators that generate intense heat and are less directable. An IR curing cell is a thermal oven that expends energy to heat the atmosphere and walls, while spilling energy into the factory. A laser curing cell operates at room temperature and requires no thermal insulation, significantly impacting the infrastructure and cost of curing.

The Cold Oven Advantage

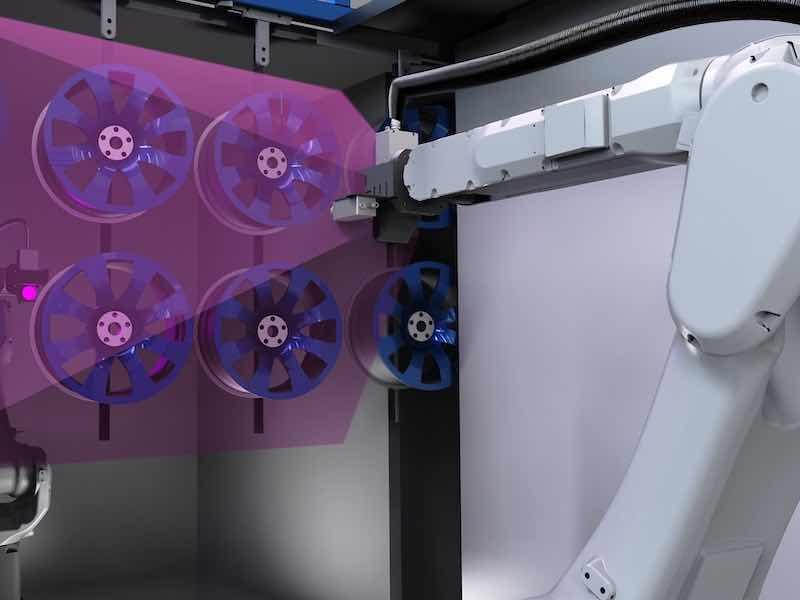

Robotic laser powder coat curing.The advantage of the cold oven is particularly significant in drying processes that require large volumes of air displacement. Another advantage of diode lasers is maintenance-free operation for at least seven years. In contrast, IR lamps wear out at varying rates, which challenges curing cell uniformity and requires frequent replacement in high-utilization installations. It can be appreciated that more frequent replacement of the excitation source translates into lost productivity, along with added consumables cost and waste disposal burden.

Robotic laser powder coat curing.The advantage of the cold oven is particularly significant in drying processes that require large volumes of air displacement. Another advantage of diode lasers is maintenance-free operation for at least seven years. In contrast, IR lamps wear out at varying rates, which challenges curing cell uniformity and requires frequent replacement in high-utilization installations. It can be appreciated that more frequent replacement of the excitation source translates into lost productivity, along with added consumables cost and waste disposal burden.

Fast curing in a room temperature environment has tangible effects on factory OpEx. Manufacturing companies who shared internal models of upcoming laser installations predict reductions in factory floor space allocation and per part OpEx by >75%, while eliminating a critical manufacturing bottleneck. At the same time, the reduction in oven size and associated HVAC infrastructure is expected to yield a ~50% CapEx reduction. Because the room temperature laser curing cells displace convection ovens heated by fossil fuel combustion, companies no longer must allocate empty factory space for curing oven evacuation during emergencies.

Volume manufacturers identify laser heating as a significant opportunity to drive their sustainability strategy.

“A key Whirlpool initiative is to reduce our overall carbon footprint and decarbonizing our manufacturing operations,” says Scot Blommel, Global Sustainability Sr. Manager for Whirlpool Corporation. “Traditional curing ovens with large burners and sprawling floor space requirements contribute significantly to energy consumption and CO2 emissions. By replacing thermal ovens with room-temperature laser curing cells, we anticipate substantial reductions. This technology aligns perfectly with our commitment to responsible manufacturing and minimizing our carbon footprint.”

Revolutionizing Whirlpool’s Production Lines

Whirlpool powder operations.Blommel suspects laser curing could revolutionize Whirlpool Corporation’s production lines.

Whirlpool powder operations.Blommel suspects laser curing could revolutionize Whirlpool Corporation’s production lines.

“Rapid laser curing will significantly increase throughput while maintaining or exceeding the high-quality finishes our customers expect,” he says.

The company imagines the possibilities of stylish doors and washer panels that can be cured in a fraction of the time, with enhanced durability and a flawless appearance.

“The compact nature of laser curing systems could save valuable facility floor space, allowing for greater flexibility and efficiency in our production layout,” Blommel says, adding the company will focus on applying laser curing to flatter components like doors and side panels, where the laser's precision and efficiency can be readily optimized.

With experience and process refinements, Whirlpool Corporation’s vision extends to complex, three-dimensional shapes such as cavities.

“This ambitious endeavor reflects our dedication to continuous improvement and leveraging innovative technologies to enhance our manufacturing capabilities and deliver exceptional products,” Blommel says. “We believe laser curing represents a true step change in appliance finishing, paving the way for a more sustainable and efficient future.”

Pushing Boundaries in Physics, Color Science, and Formulation

PPG’s chemists and engineers are developing new powder coatings ideally suited to laser curing.While laser heating is already slated for widespread industrial adoption in 2025, the story is only beginning. The step changes in curing efficiency and sustainability lasers offer have all been achieved on coatings not engineered with lasers in mind. Behind the scenes, PPG’s physics, color science and formulation experts have begun to push the boundaries.

PPG’s chemists and engineers are developing new powder coatings ideally suited to laser curing.While laser heating is already slated for widespread industrial adoption in 2025, the story is only beginning. The step changes in curing efficiency and sustainability lasers offer have all been achieved on coatings not engineered with lasers in mind. Behind the scenes, PPG’s physics, color science and formulation experts have begun to push the boundaries.

“Our team of chemists and engineers will discover ways to reduce the time and energy input required to melt and cure, while balancing properties that PPG’s customers around the world have come to expect,” says Luis Fernández, PPG’s Global Technical Director, Industrial Coatings.

Altogether, industrial heating processes can account for up to 10% of the total industrial carbon footprint and energy consumption, which motivated the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Industrial Efficiency and Decarbonization Office (IEDO) to award $1.2M of federal funding to a consortium led by the Lawrence Technological University including Whirlpool Corporation, PPG Industries and IPG Photonics. During the three-year project, the consortium members plan to model, implement and realize the extraordinary promise of lasers for fast room-temperature curing of powder coat. Fernández summarizes, “the collaboration between IPG Photonics and Whirlpool in laser curing is just another example of how PPG uses innovation to help our customers meet their productivity and sustainability goals.”

Chance Willis is Business Development Manager for Coatings at IPG Photonics Corporation, in Marlborough, Massachusetts. Luis Fernández is Global Technical Director for Industrial Coatings at PPG Industries in Allison Park, Pennsylvania. Michael Cukier is Principal Engineer for Global Advanced Manufacturing Engineering at Whirlpool Corporation in Benton Harbor, Michigan.

References

[1] Abhinandan, L.; Chari, R.; Nath, A.K. and Trivedi, M.K., Laser curing of thermosetting powder coatings: A detailed investigation, J. Laser Appl, 11, 6, 1999.

[2] Schmitz, C.; Strehmel, B., Photochemical Treatment of Powder Coatings and VOC-Free Coatings with NIR Lasers Exhibiting Line-Shaped Focus: Physical and Chemical Solidification, ChemPhotoChem, 1, 2017, 26.

[3] Giampieri, A.; Ling-Chin, J.; Ma, Z.; Smallbone, A.; Roskilly, A.P., A Review of the current automotive manufacturing practice from an energy perspective, Applied Energy, 261, 114074, 2020.

[4] Simone, G., An experimental investigation on the laser cure of thermosetting powder: An empirical model for the local curing, Prog. Org. Coatings, 68, 2010.