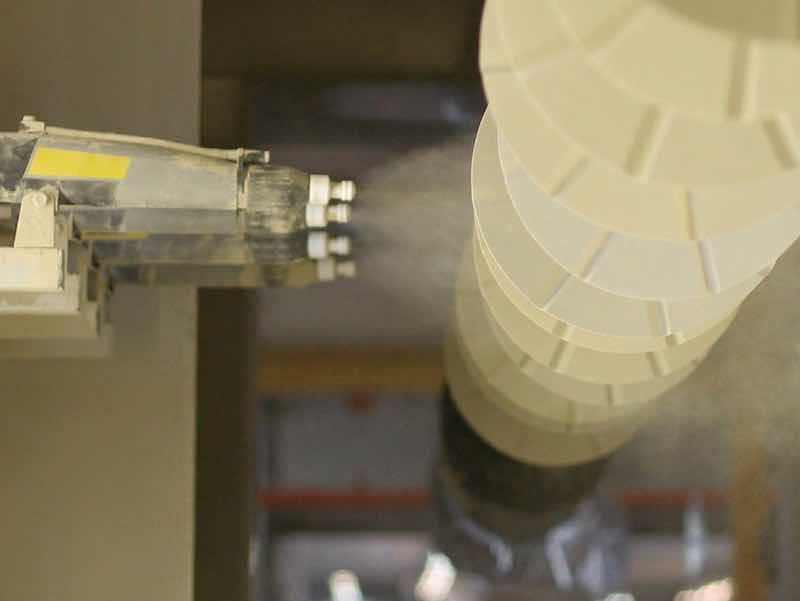

We all know applying powder coatings can sometimes be tricky.

Fiona Levin-SmithSometimes, jobs go wrong. For every coating that comes out perfect, there will be a reject down the line somewhere. The more experience you gain, the risks of a blundered coating are reduced, and we’re here to nudge a bit more knowledge your way. We talk about appearance issues in another guide which you can see here, but right now, we are going to dig into application issues. This is when issues arise in the actual process of applying a powder coating to a substrate, the result of which is often a reject.

Fiona Levin-SmithSometimes, jobs go wrong. For every coating that comes out perfect, there will be a reject down the line somewhere. The more experience you gain, the risks of a blundered coating are reduced, and we’re here to nudge a bit more knowledge your way. We talk about appearance issues in another guide which you can see here, but right now, we are going to dig into application issues. This is when issues arise in the actual process of applying a powder coating to a substrate, the result of which is often a reject.

As you will read, there is a host of potential issues, many of which stem from not having good ground. Gun settings, film build, improperly maintained equipment, and gun to part distance can all affect an application negatively as well. There are more, and we’ll get into them all, starting with...

Poor Charge, Low Film Build, and Insufficient Wrap

This trio of issues is like a terrible three-in-one package. All of the above, either alone or together can cause the coating to look bad. Quite often a grainy effect, or tight orange peel, is what you end up with. This can often be caused by low film build, as, simply put, there’s not enough coating on the part to create the nice smooth surface you’re looking for. Plus, if you have a low film build with certain colors, you will see the substrate right through it – yellows and whites are often the culprits.

The Problem

The most common cause of these issues is poor grounding. Now, there is an EFTA standard for what your ground should be, and if that is not met, no matter how you fiddle with your gun settings or gun to surface distance, the powder just will not take a charge; keep this in mind for the rest of the guide, because good ground is going to pop up a lot. Of course, ground is not the only factor in this issue. Your gun settings may actually be the problem. Too much powder flow and incorrect kV levels can affect an application for the worse.

The Fix

Straight away, make sure that you have a good earthen ground. There needs to be some kind of connection from your part – the substrate being coated – to that earthen ground, be it racks or hangers etc. Also, ensure that these connecting parts are clean, because if there is not good metal to metal contact the charge will not pass through as easily. Truthfully, a regular maintenance and cleaning system is a good process to have in place. Powder builds up on racks, electrodes, and hooks, and needs to be cleaned away regularly – i.e.: don’t just paint until you can’t paint anymore and then grind it down.

Now, for the gun settings: check your kV levels and powder flow, especially with consideration to what each individual powder requires. If you do fiddle with the settings frequently and see this application issue crop up, double-check the Technical Data Sheet or call up your supplier for the correct kV and flow settings.

Depending on how old your equipment is, something may have actually broken in the gun itself. Multipliers, cables, pumps, and boards can all go bad, basically. You can physically check the kVs coming out of your gun with a kV Meter. A decent one can be picked up for under $50. You will also want to make sure that no powder is getting into where it shouldn’t, like the controls of your equipment. That is just a whole mess of trouble waiting to happen.

As for flow...if your gun is spraying too much powder it can cause you not to get the proper charge, and will waste a lot of product. Another thing that can cause powder wastage, and improper application, is the humidity in the room. Too much or too little humidity can interfere with the spraying process. You want to try and maintain a constant temperature or relative humidity – both in the storage areas and application rooms. Ideally, the range to keep in is between 50+/- 10 for humidity and 70°+/- 10° for temperature.

Reclaiming powders can cause issues. If the particles are too small, they will not carry a charge as easily. Maintain a proper ratio of virgin to reclaim and you can avoid issues arising due to this particular factor.

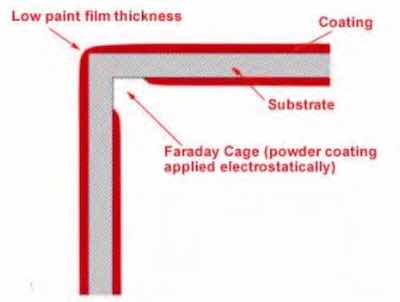

Poor Penetration of Powder into Faraday Cage Areas

This can be a tricky issue to get your head around. Basically, when parts have internal corners or an odd geometry, due to how the electrostatics travel through the metal, the powder will not apply to these areas easily. This is called a Faraday Cage. The powder is, in a word, stubborn, and will want to pull away from the corners towards the flat areas or edges. This results in areas of a surface that are left bare of powder – usually the corners or recesses and once cured, leave such areas vulnerable to corrosion.

This can be a tricky issue to get your head around. Basically, when parts have internal corners or an odd geometry, due to how the electrostatics travel through the metal, the powder will not apply to these areas easily. This is called a Faraday Cage. The powder is, in a word, stubborn, and will want to pull away from the corners towards the flat areas or edges. This results in areas of a surface that are left bare of powder – usually the corners or recesses and once cured, leave such areas vulnerable to corrosion.

The Problem

Most of us who have worked with powder have come across the Faraday Cage effect! They are difficult and frustrating to deal with, but what causes them? As it turns out, a whole lot of things can be the cause. Grounding and gun settings, like we covered above, but also not enough powder flow, gun to part distance, poor spray pattern, and too fine powder can produce a Faraday Cage effect.

The Fix

There are some methods to preventing and working around a Faraday Cage effect, and we will start with powder flow. If you do not have enough powder coming out of the gun itself, it is going to make it even harder to get the powder into those internal corners. If this is the case, adjust your flow and increase the amount of powder leaving the gun.

There are some methods to preventing and working around a Faraday Cage effect, and we will start with powder flow. If you do not have enough powder coming out of the gun itself, it is going to make it even harder to get the powder into those internal corners. If this is the case, adjust your flow and increase the amount of powder leaving the gun.

Now, gun to part distance. You need to mind how much time you spend with the gun, especially so with automatic systems, and where it is positioned with respect to the part. You cannot just push a part through the application and expect the Faraday Cage areas to be filled. What it boils down to is pay attention to your gun. The tip can wear out, or a clot can form on the end – both issues can spoil how the powder will exit the gun.

Again, if your reclaimed powder is too fine, it will not carry a charge as well, meaning the risk of a Faraday Cage is increased. Check your mix of virgin to reclaim powder.

This is not an end all solution to beating a Faraday Cage, but heating the substrate before spraying can help the powder disperse more evenly into those tough areas. Doing this increases the overall film build and how well powder grips to the internal corners.

Back Lonization and kV Rejection

Each part is only capable of taking so much charge. Go over that amount, and it will start to reject the charge. This results in the coating behaving differently, kind of like it is standing up or looks different in that area, and once it is cured, you will see the defect in that area of the part. Worse still, you can get back ionization. In itself, back ionization gives a ruddy look to a coating, but this whole application issue can take on a number of unpleasant appearances, including orange peel and starring. Not a good look, and not a good outcome.

Each part is only capable of taking so much charge. Go over that amount, and it will start to reject the charge. This results in the coating behaving differently, kind of like it is standing up or looks different in that area, and once it is cured, you will see the defect in that area of the part. Worse still, you can get back ionization. In itself, back ionization gives a ruddy look to a coating, but this whole application issue can take on a number of unpleasant appearances, including orange peel and starring. Not a good look, and not a good outcome.

The Problem

Poor grounding and too fine powder can contribute to this application issue, for the same reasons we have highlighted above, though they are not the main suspects. Mostly, what causes such a reject to form is forcing a part to accept more charge than it can handle, or continuing to apply powder once that limit has been overloaded.

The Faraday Cage issue can be a factor here as well. Due to the way the electrostatics work and how the powder attracts to some areas more readily than others, it is easy to accidentally over- apply powder in the areas not suffering from the Faraday Cage effect. These areas with too much powder will suffer from back ionization and from defects like orange peel. Back ionization can form when your gun to part distance, kVs, and microamps aren’t monitored closely enough. Even if true back ionization does not develop, you still might lose some of the smoothness in the finish.

The Fix

As before, check for good ground. Reducing your micro amps and kV settings can help get around this application issue, as can decreasing your powder flow. Taking these steps will lower the load and voltage that you are applying to the substrate.

An ideal gun to part distance is typically eight to ten inches on automatic lines. Handguns are slightly different but don’t go thinking that you need to stick the nozzle right to the part – that will blow off more powder than it applies. Spraying by hand is something that experience will help with, but a good rule of thumb is to keep the distance around 6-10 inches.

Gun Spitting, Surging, and Inconsistent Powder Feed

It is hard to withhold a scream of rage when, right in the middle of an application, your gun spits out a wad of powder and ruins an otherwise good coating. It is blindingly frustrating when your gun surges with a sudden influx of powder. This group of issues is definitely what one might define as a pain in the backside, as they result in uneven coatings with a marred finish.

It is hard to withhold a scream of rage when, right in the middle of an application, your gun spits out a wad of powder and ruins an otherwise good coating. It is blindingly frustrating when your gun surges with a sudden influx of powder. This group of issues is definitely what one might define as a pain in the backside, as they result in uneven coatings with a marred finish.

The Problem

Too much fluidization is possibly the biggest player here. What happens is that there is way too much fluidization going on in the fluidizing hopper and you are getting lots of air bubbles. This means that the flow coming out of the gun is not a consistent mix of air and powder; there is too much air. What else can cause surges and spits though?

Glad you asked! Build upon the tip of the gun, and on the electrode, can cause spits when that residue build up decides to break off all at once. Also, worn out pumps or venturi tubes can contribute here, as can kinks in the hose – and if your hose is really long that can factor in too, as the longer the hose, the more air, power, and powder it needs for a consistent flow.

Humidity can affect your air as well. Water in the airline will mess everything up, creating impact fusion or powder clumping – all of this causes spitting as the clumps come loose. Essentially, the more moisture in the air, the heavier the powder will become as it pulls the water particles in.

The Fix

Depending on how new your equipment is, hose length has already been factored in by the manufacturer, as some automatic booths have different settings for each hose depending on how long they are. The best thing to do is to check with your equipment manufacturer what the ideal hose length should be for your system. So, to prevent spits, surges, and inconsistent powder feed, check your equipment, make sure the hoses themselves are not being restricted in any manner, do not go crazy with the fluidization and clean your equipment regularly.

Reclaimed powder does not act the same as virgin powder. It does not fluidize as well as virgin, nor does it travel through hoses or charge as well. This makes it more likely to have these application issues. Judge whether or not the benefits of reclaiming powder outweigh the risks depending on what your job shop and clients require.

Poor Spray Pattern

This is a pretty straightforward issue, caused, by and large, by not maintaining equipment to the degree it requires. The powder does not spray out of the gun evenly, causing inconsistency in film build and pigmentation.

The Problem

Let’s face it, equipment gets well used and gets old. Poor spray patterns can arise when parts of your gun, hoses, and pumps aren’t cleaned properly or have just come to the end of their life. Sometimes, this shows as powder residue building up in the equipment. Other times, the flow is not as strong or consistent as it should be, meaning a worn or broken pump.

Some companies make equipment with air settings geared towards spray patterns. If you are having issues, go over the manual or talk to your manufacturer.

The Fix

Easy problem, easy solution. All you have to do is narrow down where the problem is and replace the part. Or, clean the part thoroughly – particularly if your equipment is part of an automatic line. Preventive maintenance is going to be your key step to avoiding poor spray patterns.

Poor Powder Thickness or Coverage

Film thickness and coverage truly affects the overall finish of a coating. Too thick, and you will run into issues like orange peel or sagging; too thin, and you will be able to see the substrate – and any blemishes on it – easily through the film. Grounding makes an unsurprising appearance as a culprit here, however improper settings on your equipment, worn equipment, improper rack design, part presentation and gun to part distance, powder flow, and low humidity all factor in as well.

The Problem

So, grounding. Yes, grounding, again, is often the problem. If you do not have good ground, you are just not going to be able to get the powder to adhere to the substrate evenly. All sorts of problems crop up, not just poor powder thickness and coverage – and not just the application issues we are talking about here either! Bad grounding also has a tendency to magnify how severely other problems form too, like how quickly and how badly back ionization can form.

Poor powder thickness and coverage also comes down to your gun settings. If you are not getting the proper kVs, you will lose film build. This, too, can pop up if the equipment is worn – check out how we covered this in the previous application issue.

One thing that we have yet to cover is poor rack design. If you are doing multiple parts at once, and they are not spaced far enough apart the powder will be pulled in different directions. Minor differences in, for example, how well each individual part is grounded, can mean that certain parts will attract more powder than others. As such, some parts will be more coated than others.

Another point to consider, with automatic lines, is that the part presentation can be a huge issue. Depending on the size and shape of the piece to coat, how it is oriented during the spraying process can really affect the film build. If the front end is six inches from the gun, and the back half is 12 inches from the gun, then you are going to get different film thicknesses on both ends.

And again, humidity will cause you to lose film build. How? Well, as the water in the air travels through the hose it builds up a static charge – a charge which is the opposite of what your gun is using to make the powder adhere to the substrate. All of this causes your film build to go down significantly.

The Fix

We will say it plainly, powder is a great insulator. The more powder that builds up on your rack, or if you are recoating a piece and there is already a layer of powder down, the part is being insulated from the ground. You will see a difference even in back to back jobs if you don’t clean the racks in between sprays. This plays into the poor rack design issue, as if some hooks are cleaner than others, the charge each part carries will differ. So! Ensure that your lovely, clean racks are well spaced for the type of piece you’re coating when spraying multiple parts at once.

Now about that part presentation...this is a tricky one to solve if you are not spraying by hand – unless you do decide to switch

over to this method for oddly shaped pieces – so your best bet is to tailor the gun settings as needed, and check your powder flow, gun to part distance, and the borders of your electrostatic equipment.

We talked about the importance of preventive maintenance above already, as well as the importance of humidity control, so we’ll just move onto our second last application issue...

Powder Sagging

We explained powder sagging in detail in one of our previous guides when we talked about appearance issues, but the gist of it is that far too much powder has been applied to a surface, creating a film so thick that during the cure it physically sags under its own weight. This is most is most common in urethane based coatings.

We explained powder sagging in detail in one of our previous guides when we talked about appearance issues, but the gist of it is that far too much powder has been applied to a surface, creating a film so thick that during the cure it physically sags under its own weight. This is most is most common in urethane based coatings.

The Problem

In the Faraday Cage section, we spoke about how heating a substrate before spraying can help powder apply better. However, heat it too much and the powder will melt and flow on contact – this can even go beyond sagging and icicle, a term applied when the coating will actually snap off like an icicle.

As for film thickness, if you have built up too much powder, as it goes through the gel and flow stages, the sheer weight of it all follows gravities bidding and, literally, sags.

The Fix

Sagging is relatively simple to avoid. Keep your film thickness to what your supplier and/or TDS specify, reduce the amount of powder coming out of your gun, and do not heat the substrate too much prior to coating the Surface.

Foaming

Our last application issue is foaming of the surface. Our experts have generally seen this occur most with urethane based powders. So what happens is, if you let your film build get too high, the Ecap gets trapped on the surface, builds and it looks like foam. Even in Primid or non-TGIC polyesters, you can get a water vapor giving a similar effect. It’s perhaps not so much like foaming but it certainly creates an unwanted effect. Either way, it is not an attractive finish.

The Problem

Foaming happens when the film build is too thick. The Ecap is trapped all over the surface of the substrate and during the cure, it tries to escape. This creates a foaming effect, or excessive pinholing, depending on your luck.

The Fix

This is an easy one. Mind your film thickness and increase the line speed or reduce the oven temperature. Dust your hands off and call it a day, buddy.

To Finish Up

Application issues pop up in any and every job shop. No matter how much experience you have, you will come across some, if not all, of these at least once in your career. They are annoying, as all rejects are, but can be prevented. As you have probably gathered from the dozen (or more?) times we mentioned it in this guide, good ground is essential to ensuring that powder adheres consistently and evenly across a surface. We cannot emphasize enough how important preventive maintenance on your equipment is too. Keep it clean, and keep it in shape!

From Faraday Cage effects to sagging to poor spray patterns, we have covered it all. Arm your job shop with this knowledge, and you will be better prepared to churn out great coatings.

Fiona Levin-Smith is Vice president of Marketing and Specification for IFS Coatings. For further questions or inquiries, visit www.ifscoatings.com