The last month seems to have yielded a spate of corrosion-related problems.

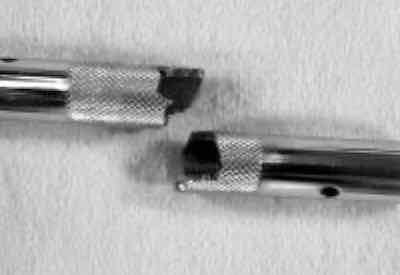

Frank AltmayerThe first problem arose very close to home when I visited my boat and found a turnbuckle snapped (Fig. 1). It seems that the boatyard had installed a nickel-chromium-plated brass turnbuckle on my “baby stay,” a small cable that runs from approximately the middle of the mast of a sailboat to the deck.

Frank AltmayerThe first problem arose very close to home when I visited my boat and found a turnbuckle snapped (Fig. 1). It seems that the boatyard had installed a nickel-chromium-plated brass turnbuckle on my “baby stay,” a small cable that runs from approximately the middle of the mast of a sailboat to the deck.

Brass is a poor choice of material for any application involving high tensile stress and a corrosive environment, because of its high sensitivity to stress corrosion failures. Indeed, this brass turnbuckle exhibited intergranular brittle failure (Fig. 2), a characteristic of stress corrosion. The correction is to replace the part with a material more suitable for the high seas (stainless steel).

Fig. 1—Snapped turnbuckle.The same day I discovered my boat’s corrosion problem, I also got involved with others that were more interesting. A plating company contacted me that utilizes a chromium-plated steel mold that needs to be cleaned frequently. Their cleaning procedure involves soaking the mold in a proprietary alkaline cleaning solution for 10–15 minutes, followed by the application of ultrasonics for approximately 2–3 hours or more, as the “stuff” in the mold is difficult to remove.

Fig. 1—Snapped turnbuckle.The same day I discovered my boat’s corrosion problem, I also got involved with others that were more interesting. A plating company contacted me that utilizes a chromium-plated steel mold that needs to be cleaned frequently. Their cleaning procedure involves soaking the mold in a proprietary alkaline cleaning solution for 10–15 minutes, followed by the application of ultrasonics for approximately 2–3 hours or more, as the “stuff” in the mold is difficult to remove.

After a few months of repeated cleaning cycles, they have noticed corrosion of the mold that appears to be limited to recessed areas and cavities. They were told that the problem may be caused by stray currents or bimetallic corrosion, and they asked if I could provide an opinion.

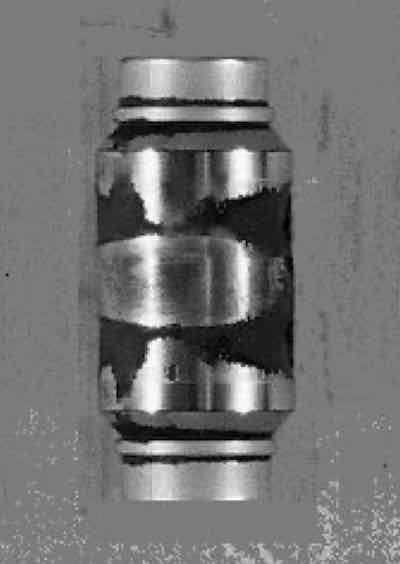

Fig. 2—Granular brittle failure.Further investigation into their operation revealed that the attack was localized and not limited to chromium-plated areas. Etching of metal became evident only after several months of tooling, processing, and repeated cleaning. The corrosion appeared to be concentrated in areas that were cavities or recessed areas on the tooling, whether chromium-plated or not (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2—Granular brittle failure.Further investigation into their operation revealed that the attack was localized and not limited to chromium-plated areas. Etching of metal became evident only after several months of tooling, processing, and repeated cleaning. The corrosion appeared to be concentrated in areas that were cavities or recessed areas on the tooling, whether chromium-plated or not (Fig. 3).

A definite line of demarcation was visible where the tooling was mounted into the molding plate, with no etching present on areas where the tooling was mounted into the plate, but severe etching immediately above the joint between the plate and the tooling.

Current operating practice is to use a proprietary cleaner in the ultrasonic tank, under the following conditions:

- The concentration of the cleaner is approximately 8 oz/gal.

- The operating temperature is approximately 180°F.

- The cleaning tank is an ultrasonic cleaning tank, 200 gal in size, and operated at an ultrasonic power density of 40 watts/gal.

- A recirculating pump on a cartridge filter provides gentle agitation/tank turnover.

- Tank temperature is maintained with heating coils mounted on the bottom of the tank, along with the ultrasonic transducers.

Did Stray Currents cause this?

Fig. 3—Concentrated corrosion.Stainless steel and chromium plating are soluble in alkaline solutions when subjected to anodic DC. Stray current could therefore cause attack of the metals. The attack, however, would be concentrated on sharp edges and ridges, which is the opposite of the observed attack at crevices.

Fig. 3—Concentrated corrosion.Stainless steel and chromium plating are soluble in alkaline solutions when subjected to anodic DC. Stray current could therefore cause attack of the metals. The attack, however, would be concentrated on sharp edges and ridges, which is the opposite of the observed attack at crevices.

Furthermore, the company's efforts to measure stray currents were unsuccessful in detecting significant levels.

Was this a Chemical Attack?

Stainless steels and chromium plating are not subject to chemical attack by alkaline cleaning solutions, in the absence of stray currents or dissimilar metals. Furthermore, the chemical attack would manifest uniformly, whereas the experienced attack was highly localized.

Did the Ultrasonics Cause This?

Stainless steels and chromium electroplate are resistant to corrosive attack by alkaline solutions, as long as a thin oxide film (which forms instantly when cleaned stainless steel or chromium is exposed to air) is present on the surface of these metals. It is possible to apply an excessive amount of cavitation intensity¹ in an ultrasonic cleaning tank, which can destroy the protective oxide film. The resulting erosion of the metal will occur over a long period and will be concentrated at cavities, where sonication is at its maximum concentration.

Cavitation intensity is dependent upon:

Temperature: Temperature changes also change the viscosity, solubility of gases, diffusion rates of dissolved gases, and vapor pressure, thereby affecting cavitation intensity. In water-based solutions, the cavitation effect is optimized at about 60 °C. Viscosity should be minimized, as syrupy liquids retard the formation of cavitation bubbles. Dissolved gases reduce cavitation effects by discharging and absorbing energy that would otherwise create implosion of cavities. Increased temperature minimizes gas solubility, maximizes the diffusion rates of dissolved gases, and brings the liquid closer to its vapor pressure. Vaporous cavitation is the most effective method of ultrasonic cleaning.

Cavitation Intensity: The intensity of cavitation is also related to the applied ultrasonic power. As the power is increased above the cavitation threshold, cavitation intensity turns “flat,” and no further increase in cleaning efficiency can be obtained by increasing applied power. The ultrasonic power must be adequate to create cavitation around the entire part being cleaned. This power is rated in “watts per gallon.” As the tank volume increases, the power required to achieve cavitation decreases. Applying too much power to a part in a large tank can cause cavitation erosion, which resembles corrosion. In tanks with a capacity above 100 gallons, the maximum power applied should be 20 watts/gal; tanks with a capacity below 100 gallons utilize exponentially increasing power densities, ranging from 20 watts per gallon to 130 watts/gal. Cavitation intensity is also inversely related to ultrasonic frequency. As the frequency increases, the cavitation intensity decreases. Power and frequency, therefore, need to be balanced.

We suspect that the current operating practice of applying 40 watts/gal for a 200-gal cleaning tank is producing an erosion of the metal in areas of maximum cavitation (recessed areas and cavities). The ultrasonic power applied to the tooling in this tank should be reduced to 20 watts/gal.

References

- “Ultrasonic Cleaning, Fundamental Theory and Application,” F. John Fuchs, Precision Cleaning, 1994.

Frank Altmayer is a Master Surface Finisher, an AESF Fellow, and the technical education director of the AESF Foundation and NASF. He owned Scientific Control Laboratories from 1986 to 2007 and has over 50 years of experience in the metal finishing industry. He received the AESF Past Presidents Award, the NAMF Award of Special Recognition, the AESF Leadership Award, the AESF Fellowship Award, the Chicago Branch AESF Geldzahler Service Award, and the NASF Award of Special Recognition.